The Napoleon III style (1852-1870)

07.07.22

A period of decadence, the Second Empire (1852-1870) sought to impose prestige through pomp, festivities, and luxury, in contrast to the bourgeois reign of the discreet Louis-Philippe . The Napoleon III style is the last style to bear the name of a sovereign, that of Louis Napoleon Bonaparte , first elected president by universal male suffrage, then prince-president before being crowned emperor in December 1852.

Considered eclectic , this style is based on a revival of past styles. Everything about it is borrowed from the styles that preceded it. Instead of drawing their inspiration from a single era, the cabinetmakers and decorators of the Second Empire drew indiscriminately, with joyful exuberance, from all sources.

This blending of styles manifests itself in the decorative arts not successively but simultaneously. The result is a richness, an abundance, an eclecticism that is sometimes excessive but which gives an impression of research and fertility.

PASTICHES AND NOSTALGIA

Pair of ewers in the Renaissance style

This taste for historicism draws on forms from all periods. From Louis XIII, ornamentalists adopted the turned, bead-like legs; from Louis XIV, the Boulle furniture with its marquetry of brass and tortoiseshell, sometimes replaced by dyed leather or dark wood; from Louis XV , the Rococo curves; and from Louis XVI , the fluted legs, finer than the originals. The work of Viollet-le-Duc also revived interest in the Middle Ages. References to earlier styles became the norm.

Cylinder desk after Riesener, attributed to the Beurdeley firm

Cylinder desk after Riesener, attributed to the Beurdeley firm

These numerous copies or adaptations of 18th-century furniture reflect a desire to renovate national palaces: the Tuileries, Saint-Cloud, Compiègne, etc. The Imperial Furniture Repository buys back antique furniture that is then put up for sale to refurnish the royal residences.

Empress Eugénie played a significant role in this historicist craze. She particularly appreciated the Louis XVI style due to her admiration for Marie Antoinette . The crown commissioned meticulous copies of antique furniture from Jean-Henri Riesener (1734-1806), notably the Louis XV roll-top desk now housed at the Palace of Versailles. Meanwhile, the Grohé brothers created a suite of furniture for the Galerie François Ier, and Jeanselme , who had taken over the Jacob firm, crafted 18th-century armchairs for the Château de Saint-Cloud. The term "Louis XVI – Empress" even emerged. Leading specialists in pastiche included Louis-Auguste-Alfred Beurdeley (1808-1882), Alexandre-Georges Fourdinois (1799-1871), and Henri Dasson (1825-1896).

Pair of Louis XVI style consoles in walnut and marble

But this return to these styles was politically motivated. By reviving the forms of the Ancien Régime, the Second Empire identified itself with the court and the established monarchy, thus lending it a degree of legitimacy. By reorganizing French industries, Napoleon III breathed new life into the decorative arts, transforming production.

FURNITURE, A REFLECTION OF AN EVOLVING SOCIETY

Meanwhile, the bourgeoisie, the dominant class of the mid-19th century, sought a certain level of comfort with a multitude of small pieces of furniture within easy reach. There was a desire for an intimate and welcoming décor, characterized by its functionality: chests of drawers, secretaries , game tables , and pedestal tables. New categories of lightweight and easily movable furniture were created: nesting tables, tilting , the "charivari" chair, and a multitude of armchairs upholstered in velvet or brocade, generally red, with braided fringes to conceal the wood (confident chairs, boudeuses, bornes, poufs, etc.).

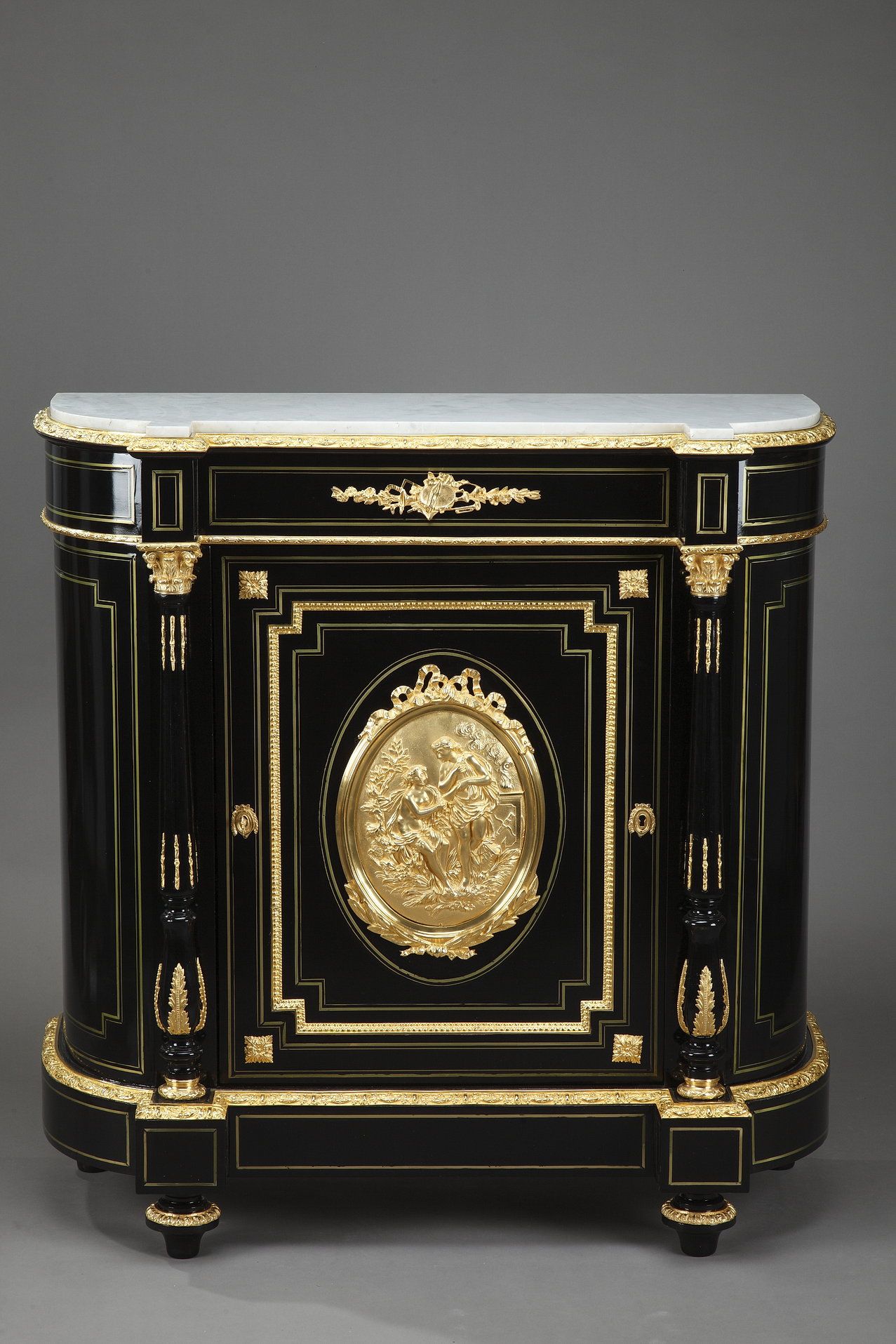

Napoleon III period sideboard in blackened wood and gilt bronze

Napoleon III period sideboard in blackened wood and gilt bronze

There was a fondness for opulence and opulence, with a taste for contrast that created an air of luxury. Furniture made of ebony or blackened pearwood was adorned with gilt bronze, marbles of every color, and Boulle marquetry with red scales. The inlay of precious woods, mother-of-pearl, ivory, and brass flourished thanks to the band saw, which allowed for extremely fine cutting. This resulted in furniture with highly precise decoration and a flawless appearance, unlike 18th-century furniture that often bore tool marks. For example, the Rivart firm developed an incredible porcelain marquetry inlaid in the veneer of its furniture.

Detail of a Boulle marquetry games table, Napoleon III period

Detail of a Boulle marquetry games table, Napoleon III period

Increasingly mass production was facilitated by the mechanization of artisans' workshops. There was a desire to reduce production costs in order to make fashion more accessible to the bourgeoisie, who were fond of designs inspired by diverse sources. This division of labor may explain the lack of innovation in forms.

However, the Universal Exhibitions in Paris, beginning in 1855, prompted a new reflection on the status of the decorative arts. Manufacturers sought to elevate them to the status of a major art form by designing furniture as works of art. This led to the increasingly frequent appearance of stamped signatures on the hidden surfaces of furniture. This is the case with our Louis XVI style commodes stamped GROHE under the marble top.

Grohé company stamp under the marble top of a Louis XVI style commode

Grohé company stamp under the marble top of a Louis XVI style commode

NEW TECHNIQUES

One of the distinctive features of the Napoleon III era , marked by a certain originality, is the use of papier-mâché with a black background. Originating in England, this technique relies on a mixture of paper, glue, and plaster, solidified under heat and molded. This material, then as hard as wood, is subsequently varnished, lacquered, and decorated. This process, often inlaid with mother-of-pearl, was adopted by French furniture makers and became widespread from 1860 onward.

Detail of Burgauté marquetry on a tilting wooden and lacquered cardboard pedestal table

Detail of Burgauté marquetry on a tilting wooden and lacquered cardboard pedestal table

burgau-patterned furniture spread , its mother-of-pearl ornaments derived from a shell called a burgau, whose interior is lined with iridescent, pearly surfaces shimmering with blue, green, and purple reflections. This technique, already used for the cradle of the King of Rome, a gift from the city of Paris Burgua-patterned furniture and seating are one of the most characteristic features of the Napoleon III style.

CONCLUSION

When Charles Garnier presented the plans for the Opéra Garnier to Louis Napoleon Bonaparte, the emperor is said to have remarked, "It's not Gothic, it's not Renaissance, it's not Classical, but what style is it?" To which the architect supposedly replied, "Napoleonic III." Perhaps he was right to assert that this style, despite its many imitations, did indeed possess its own distinct and perfectly recognizable identity.

Bibliography

- French furniture, Napoleon III, 1880s, Odile Nouvel Kammerer, 1996

- Recognizing period furniture, Pierre Faveton, 2014

- The Style Guide, Museum of Decorative Arts, Jean-Pierre Constant, Marco Mencacci, 2018